The Air Force and Nasa: Partnership in Space (1958-1969)

It was the middle of March when President Donald Trump mentioned the prospect of creating a new branch of the military, a “Space Force.” It was immediately the subject of ridicule and conjured up visions of Star Wars Stormtroopers with laser guns fighting galactic battles in space. Once again, on May 1st, the idea was suggested at a ceremony held at the White House to honor the football team of the Army’s military academy, West Point. This time, the details seemed to be a bit more serious.

Forty-nine days later on June 18, 2018, the president signed an executive order directing the Pentagon to create a sixth branch of the military solely dedicated to protecting space-based assets, and presumably ready to proactively engage in offensive measures against potential enemy’s satellites, and space-based weapons.

“I am hereby directing the Department of Defense and Pentagon to immediately begin the process necessary to establish a space force as the sixth branch of the armed forces. Our destiny beyond the Earth is not only a matter of national identity but a matter of national security.”

Trump went on to describe space as “a war-fighting domain just like the land, air, and sea.”

For some, it may have seemed like a long time coming. For others, it was nothing more than the creation of another government bureaucracy. Unlike America’s space efforts with NASA and the Air Force performing distinct functions, the line between the civilian and military in China and Russia’s space programs is non-existent. While around the globe, the list of space-capable nations is rising, not all on friendly terms with the United States. Several, like North Korea and Iran, are capable enough to launch and explode rockets that could create space debris clouds resulting in damage to critical allied space communications and GPS satellites needed in a conflict. There is the threat from Russia which recently made headlines for what is believed existing on orbit maneuverable satellites classified as “inspectors” that could observe, collide, or otherwise disable other satellites.1 That’s not to say that the U.S. is behind in the utilization of space as a military platform, it’s just that the threat is evolving, and becoming more dangerous.

The history of anti-satellite weapons goes back to the beginning of the space age. For a variety of reasons, it seemed to retreat from the forefront  through the decades with both the U.S. and Russia continuing to hide from public view the development of a myriad of space weapons. It came to the forefront again when President Reagan proposed what came to be known as the Star Wars missile defense program. The threat seemed to recede once again until in 2007 when China launched a ground-based missile and successfully took out one of their old weather satellites.3 In a high stakes response a year later, the United States Navy fired an interceptor rocket from an Aegis cruiser and successfully hit one of its own non-functioning satellites.

through the decades with both the U.S. and Russia continuing to hide from public view the development of a myriad of space weapons. It came to the forefront again when President Reagan proposed what came to be known as the Star Wars missile defense program. The threat seemed to recede once again until in 2007 when China launched a ground-based missile and successfully took out one of their old weather satellites.3 In a high stakes response a year later, the United States Navy fired an interceptor rocket from an Aegis cruiser and successfully hit one of its own non-functioning satellites.

Here we are today, with more threats, continued advances in technology, and increasingly more players in the space arena. Currently, the U.S. Air Force “Space Command” is in charge of “space efforts” on behalf of the military. It receives the majority of Defense Department funding, about $12.5 billion for FY 2019.2 What is not counted in those dollars are any “off the books” projects and the operational and support costs baked into existing DOD manpower budgets. By the time it is all counted, the total military space budget likely exceeds what NASA itself is currently allocated.

The U.S. civilian and military space programs had a long history of partnering before heading down separate roads and arriving today at what is proposed as a more focused and independent military space force. What follows is a brief history of the early days of NASA and the Air Force’s partnership in space.

The Beginning

As World War II ended, the race began to utilize the weapons of war Germany had developed. Germany had provided the world a glimpse of future battles and the new face of warfare. Ballistic and cruise missiles demonstrated the potential that the weapons of space, even at their rudimentary beginning, could have in war. While the age of modern rocketry was born of wartime needs, others dreamed it could take humans to the stars. Among the documents recovered after the war were the plans for winged rockets that would soar into space and reenter as high-speed bombers over an unsuspecting America, and vehicles that would take humans to orbiting space stations and then on to Mars.

As World War II ended, the race began to utilize the weapons of war Germany had developed. Germany had provided the world a glimpse of future battles and the new face of warfare. Ballistic and cruise missiles demonstrated the potential that the weapons of space, even at their rudimentary beginning, could have in war. While the age of modern rocketry was born of wartime needs, others dreamed it could take humans to the stars. Among the documents recovered after the war were the plans for winged rockets that would soar into space and reenter as high-speed bombers over an unsuspecting America, and vehicles that would take humans to orbiting space stations and then on to Mars.

Through the works of Werner Von Braun and the Nazi rocket program, Germany had achieved a twenty-five-year advantage over any other nation in the use of advanced rocketry.4 As the war ended, the United States and the Soviet Union would divide the Third Reich’s intellectual property and begin their own programs to fulfill the vision of using rockets in peace and in war. In those first years of the space race, there would be procrastination by the U.S. and urgency by the Soviets to find a way to use space power to thwart the American military machine. As a result, the U.S. would stumble and be surprised by the Soviet detonation of a nuclear weapon in 1953. Then in 1954, the U.S. was deceived by the Soviets into thinking a bomber gap existed with the previously unknown appearance of the Bison jet bomber in seemingly surprise numbers. The miscalculation that they were being mass-produced forced America to respond with building more B-52s.5 Finally, in

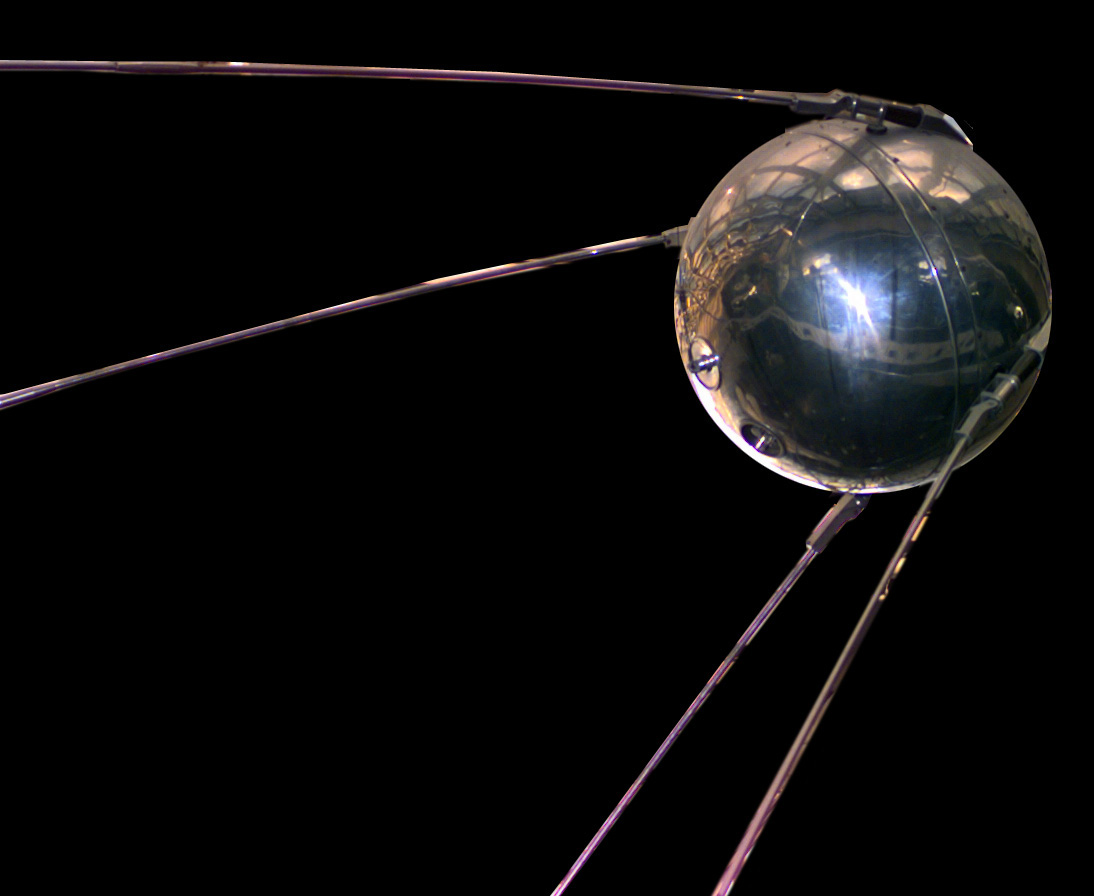

1957, the biggest upset of all, upstaged by the Soviets launch of Sputnik and  the fear in America that a missile gap had developed and the U.S. has fallen technologically behind its ideological rival.

the fear in America that a missile gap had developed and the U.S. has fallen technologically behind its ideological rival.

How America would respond to these threats would create rivalries between the branches of the service, and lead to the creation of NASA, the civilian space agency. It would eventually result in the U.S. Air Force taking the lead as the country’s dominating military space power. America’s future in space would be intertwined with the success of both organizations to coordinate and leverage each other’s work and technology that would culminate with the U.S. surpassing the Soviets and reaching the moon.5

Space Power on the Back Burner

Fresh from victory in World War II, the America military juggernaut stood alone on the global stage as the technology leader and manufacturing giant that could wage conventional war with staggering capabilities and one that could arm allied nations and devastate their enemies. Germany’s research and weapon advancements had changed the perception of how wars would be fought and how space technology and weapons could be used not just offensively, but also to deter war. In capturing the spoils of war, America gained the leading experts on German rocketry and an invaluable set of working hardware and plans. The leadership in America saw rocket weapons as attractive, but not a replacement for tanks, planes, bombers, and carriers. America would allow the Von Braun team to languish at Fort Bliss, Texas, while the Soviets gained momentum.6 The Soviets realized the American advantage and viewed rockets as the force equalizer that could negate America’s conventional forces.

In the early days of what would become the modern space age, America would be confused on what direction to take. The Army saw rockets as battlefield weapons that could be used against short-range targets7, the Navy saw satellites and even manned space stations as a way to help monitor fleet activities, as the Air Force focused on intercontinental missiles and putting its own men in space. It would finally take the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik before American began to coordinate its space activities.

The Early Days of Space

When Sputnik became the first man-made object to reach space, the shockwaves reverberated 8 throughout America. The general American sentiment was that if the Soviets could fly a satellite overhead, they could certainly do the same with a bomb. President Dwight Eisenhower dismissed Sputnik “as one small ball in the air”.6 The public was less forgiving of America as a country that followed rather than led when it came to breakthrough technologies. The U.S. would respond a few months later with a more capable satellite on an Army rocket that was little more than an advanced version of the V-2. That successful launch came after an embarrassing failed launch by the Navy with Vanguard 1. That botched attempt brought ridicule with names given to the event as “Flopnik” and “Kaputnik”. Eisenhower wanted to consolidate all U.S. rocket projects, defense, and civilian, under the wing of the Defense Department’s ARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency. Vice President Richard Nixon and Eisenhower’s Science Advisor James Killian persuaded him to pursue another course, dividing the growing space need under three umbrellas: civilian, defense, and reconnaissance.8 With the public’s apprehension still at a high, Eisenhower agreed. Mainly to appease the public outcry, Eisenhower created NASA in October of 1958 to handle civilian activities in space. The 1958 legislation that created NASA would divide America’s space mission between NASA to handle civilian space activities and the Air Force to handle military space needs. Eisenhower had strong reservations about the creation of the agency. While the value of space power would soon pay off for the military, creating a civilian agency that would target sending humans into space he thought was a waste of public resources.

When Sputnik became the first man-made object to reach space, the shockwaves reverberated 8 throughout America. The general American sentiment was that if the Soviets could fly a satellite overhead, they could certainly do the same with a bomb. President Dwight Eisenhower dismissed Sputnik “as one small ball in the air”.6 The public was less forgiving of America as a country that followed rather than led when it came to breakthrough technologies. The U.S. would respond a few months later with a more capable satellite on an Army rocket that was little more than an advanced version of the V-2. That successful launch came after an embarrassing failed launch by the Navy with Vanguard 1. That botched attempt brought ridicule with names given to the event as “Flopnik” and “Kaputnik”. Eisenhower wanted to consolidate all U.S. rocket projects, defense, and civilian, under the wing of the Defense Department’s ARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency. Vice President Richard Nixon and Eisenhower’s Science Advisor James Killian persuaded him to pursue another course, dividing the growing space need under three umbrellas: civilian, defense, and reconnaissance.8 With the public’s apprehension still at a high, Eisenhower agreed. Mainly to appease the public outcry, Eisenhower created NASA in October of 1958 to handle civilian activities in space. The 1958 legislation that created NASA would divide America’s space mission between NASA to handle civilian space activities and the Air Force to handle military space needs. Eisenhower had strong reservations about the creation of the agency. While the value of space power would soon pay off for the military, creating a civilian agency that would target sending humans into space he thought was a waste of public resources.

The Army, coming off the success of having designed the rocket that put  America’s first satellite in orbit, would now transfer their rocket team to the newly formed NASA. The Jupiter rocket that lifted Explorer into orbit was overkill for the Army’s needs, but a direct reflection of the skilled resources that had been working on the project. Meanwhile, the Air Force and Navy continued to pursue their independent programs, but the Navy would eventually transfer its efforts to the Air Force entirely by 1963. As Eisenhower left office and Kennedy’s New Frontier began, the Soviets would continue to upstage America with the launch of the first man in space, and the first man to orbit the Earth. Before NASA’s first flight, the newly formed agency eyed the moon; to succeed they would need a strong partnership with the Air Force. The Air Force would supply NASA with ground support during the countdown, liftoff, flight, and recovery and provide NASA with man-rated boosters converted from ICBMs; namely, the Atlas and Titan II.4 The Air Force also tested components for its own space needs on NASA missions. NASA’s approach to space was to compete publicly with the Soviets on headline grabbing human endeavors in space, while the Air Force eyed a strategic military advantage.

America’s first satellite in orbit, would now transfer their rocket team to the newly formed NASA. The Jupiter rocket that lifted Explorer into orbit was overkill for the Army’s needs, but a direct reflection of the skilled resources that had been working on the project. Meanwhile, the Air Force and Navy continued to pursue their independent programs, but the Navy would eventually transfer its efforts to the Air Force entirely by 1963. As Eisenhower left office and Kennedy’s New Frontier began, the Soviets would continue to upstage America with the launch of the first man in space, and the first man to orbit the Earth. Before NASA’s first flight, the newly formed agency eyed the moon; to succeed they would need a strong partnership with the Air Force. The Air Force would supply NASA with ground support during the countdown, liftoff, flight, and recovery and provide NASA with man-rated boosters converted from ICBMs; namely, the Atlas and Titan II.4 The Air Force also tested components for its own space needs on NASA missions. NASA’s approach to space was to compete publicly with the Soviets on headline grabbing human endeavors in space, while the Air Force eyed a strategic military advantage.

The Air Force Eyes Men in Space

The creation of NASA would do nothing to stop the Air Force’s ambitions of putting humans into space.10 The Germans showed interest in the idea of a “space bomber” that could target America, but time would run out in the war before the concept could be developed. Now, the Air Force would pursue its own version called Dyna-Soar, short for “Dynamic Soaring.” Dyna–Soar had been planned as a strategic weapons system capable of reconnaissance, repairing satellites, damaging enemy satellites, bombing, and capable of bringing offensive weapons to space.5 It was a small delta wing vehicle that would be manned and reusable.

The creation of NASA would do nothing to stop the Air Force’s ambitions of putting humans into space.10 The Germans showed interest in the idea of a “space bomber” that could target America, but time would run out in the war before the concept could be developed. Now, the Air Force would pursue its own version called Dyna-Soar, short for “Dynamic Soaring.” Dyna–Soar had been planned as a strategic weapons system capable of reconnaissance, repairing satellites, damaging enemy satellites, bombing, and capable of bringing offensive weapons to space.5 It was a small delta wing vehicle that would be manned and reusable.

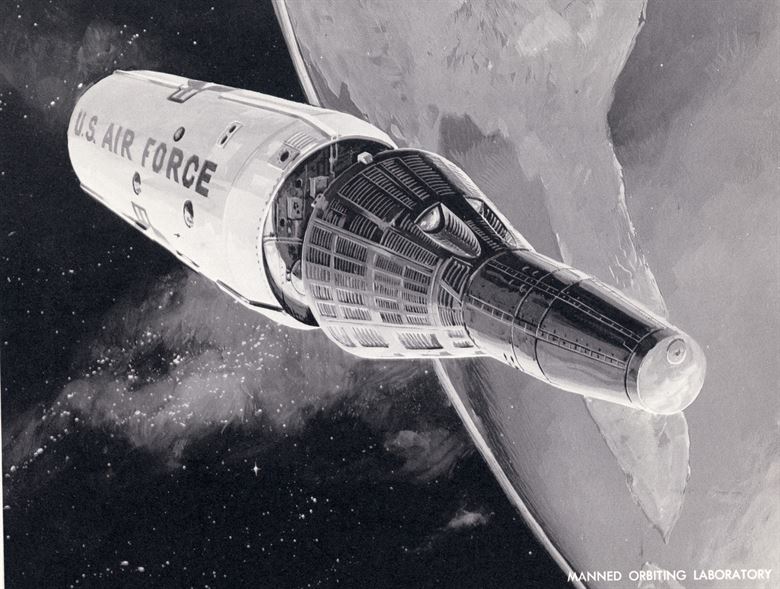

At first, Dyna-Soar was to be a suborbital glider, and then grew to be a fully orbital craft that would return to Earth and land on a conventional runway. The change in purpose was significant. Rather than perform as a “hit and run” bomber, Dyna-Soar could stay in orbit to conduct research, observation or other research as the Air Force needed. While Dyna-Soar was in discussion, the Air Force also contemplated its own manned space station called the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL). Perched atop a Titan rocket, Dyna-Soar could be the vehicle to take Air Force personnel to and from their space station.

space. Eugen Sanger, a German scientist who did not come to America after the war, would be the man conceptually responsible for the Air Force’s first attempt at manned flight. Sanger had developed early concepts for a reusable space plane.

While the Air Force refined concepts for its manned space program, NASA had begun its march to the moon with the Mercury and Gemini programs. America appeared to be on track with two parallel programs that would develop the skills and assets to create a versatile civilian and military presence in space. Though the Air Force had changed the design and function of Dyna-Soar from a one-man bomber to a research vehicle, the stigma remained. The direct militarization of space was something Eisenhower and Kennedy alike had hoped to avoid.

The Changing of the Guard

The man who became President and set America on a course to the Moon  would be assassinated on November 22, 1963. His famous challenge to land on the moon and return them safely would be a mantra his successors would carry-on. However, with the death of Kennedy came new ideas and a new vision for America that would impact the efforts in space. Lyndon Johnson canceled the Air Force’s Dyna-Soar project just weeks after becoming President.10 It would be canceled partly due to the unease of introducing a vehicle that would be viewed as a weapons platform, but mainly because NASA’s success with Gemini had negated the need for another launch vehicle. Canceling of Dyna-Soar

would be assassinated on November 22, 1963. His famous challenge to land on the moon and return them safely would be a mantra his successors would carry-on. However, with the death of Kennedy came new ideas and a new vision for America that would impact the efforts in space. Lyndon Johnson canceled the Air Force’s Dyna-Soar project just weeks after becoming President.10 It would be canceled partly due to the unease of introducing a vehicle that would be viewed as a weapons platform, but mainly because NASA’s success with Gemini had negated the need for another launch vehicle. Canceling of Dyna-Soar

Soar came on the advice of Johnson’s Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, but Johnson agreed to consider the Air Force’s request for construction of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory.11 MOL would use existing Gemini spacecraft and a habitat that would be launched with the vehicle. Astronauts would crawl through a hatch in the heat shield to access the lab and would be able to stay on board for up to thirty days to conduct experiments. The U.S. Air Force pitched the MOL as a way for the military to explore the usefulness of having their own dedicated personnel and equipment in space. On August 25, 1965, Johnson, after twenty months of deliberation, gave the go-ahead for the Air Force to begin development of the MOL. Publicly, the Air Force praised Johnson’s decision “as one of the most significant political decisions of the space age….ranking in importance with the May 25, 1961, announcement by President Kennedy of the Apollo moon landing program”.11 The MOL seemed on track to become America’s first space station and was scheduled for its first flight in late 1968, but the effort did not go unnoticed in the Soviet Union. Much like the Soviet’s early success in space served as a motivator for the U.S. program to reach for the moon, Johnson’s announcement of a military space station became the justification for the Soviets to begin a military manned space station project, codenamed Almaz.

A New Era of Space Begins

Nineteen Sixty-Nine would be a year of great success for the American space program. In July, the space race had officially come to a close as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon and returned safely to the Earth fulfilling Kennedy’s challenge. 12 There would also be another change in Presidential leadership, as continued problems at home and with the Vietnam War raging abroad forced Lyndon Johnson to forego seeking another term as President. Richard Nixon, the man who just ten years earlier advocated for the creation of NASA, would now control the future direction of the agency. Nixon would quickly make a series of decisions related to the space program that would cripple it for decades to come. First, the Air Force’s MOL program was canceled. The Air Force had underestimated the complexity of building and operating a manned space station. The project was over budget and behind schedule. It had missed its first launch date by a year and a new expects launch date was nowhere in sight. Officially, the reasons cited were that orbiting satellites had eliminated the need for manned observation platforms. Had the MOL project remained on schedule or had it not suffered the 20-month delay due to Johnson’s indecision about the effort, it may have gotten off the ground and been spared Nixon’s ax.

Nineteen Sixty-Nine would be a year of great success for the American space program. In July, the space race had officially come to a close as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon and returned safely to the Earth fulfilling Kennedy’s challenge. 12 There would also be another change in Presidential leadership, as continued problems at home and with the Vietnam War raging abroad forced Lyndon Johnson to forego seeking another term as President. Richard Nixon, the man who just ten years earlier advocated for the creation of NASA, would now control the future direction of the agency. Nixon would quickly make a series of decisions related to the space program that would cripple it for decades to come. First, the Air Force’s MOL program was canceled. The Air Force had underestimated the complexity of building and operating a manned space station. The project was over budget and behind schedule. It had missed its first launch date by a year and a new expects launch date was nowhere in sight. Officially, the reasons cited were that orbiting satellites had eliminated the need for manned observation platforms. Had the MOL project remained on schedule or had it not suffered the 20-month delay due to Johnson’s indecision about the effort, it may have gotten off the ground and been spared Nixon’s ax.

Nixon was increasingly burdened with the escalation of the Vietnam War and problems with the economy. Within a year of taking office, he sought to cut NASA’s budget dramatically. Initially, Nixon wanted to end all manned space flight in favor of unmanned missions but was convinced to build the Space Shuttle on the promise that it was the cheapest option for spaceflight.13 The Space Shuttle would undergo numerous design changes to accommodate Air Force and NASA requirements, but ultimately would not fully meet either’s needs. The shuttle’s first flight would end up being more than a decade away. NASA and the Air Force stand down for years waiting for its arrival.

In anticipation of the shuttle’s arrival, the Air Force began selecting  astronauts that would fly classified and dedicated missions. They also began construction of a shuttle launch facility at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. When the shuttle finally flew in April 1981, it fulfilled the Air Force’s original dream of a winged reusable vehicle, but the complexities of the shuttle often meant delays. The promised flight schedule proved difficult to achieve, and while the Air Force did fly several classified missions, the compromises made a decade earlier in the design, and the Challenger accident forced the Air Force to return to unmanned launch vehicles. The shuttle was no longer reliable and had difficulty meeting the demands placed upon it. No Space Shuttle launch would ever use Vandenberg facility for a launch.

astronauts that would fly classified and dedicated missions. They also began construction of a shuttle launch facility at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. When the shuttle finally flew in April 1981, it fulfilled the Air Force’s original dream of a winged reusable vehicle, but the complexities of the shuttle often meant delays. The promised flight schedule proved difficult to achieve, and while the Air Force did fly several classified missions, the compromises made a decade earlier in the design, and the Challenger accident forced the Air Force to return to unmanned launch vehicles. The shuttle was no longer reliable and had difficulty meeting the demands placed upon it. No Space Shuttle launch would ever use Vandenberg facility for a launch.

Conclusion

For a brief time during the space race, the combination of NASA and the Air Force seemed a potent force that would create for America a well-rounded space capability from winged space planes to space stations to lunar landers. The space race and the growing unrest at home and abroad would force tough decisions that would end up affecting both space programs. NASA would go on to reach the moon and fulfill Kennedy’s goal, but nearly be disbanded and forced to stay in low-earth orbit for decades to come.

The Air Force’s dreams of manned spaceflight evaporated. The Dyna-Soar program, though it had never taken flight, managed to continue to contribute to future projects. Thirty-three of the sixty-six projects related to reusable spaceplane technology continued and produced valuable spinoffs, or the products were used in Apollo and the Space Shuttle. Nixon’s cancellation of MOL wasted the years of effort and expense that went into the project. While justified on the grounds that indeed satellites had replaced the need for human observation platforms, its cancellation reflected shortsightedness regarding the other potential uses of an orbiting outpost. Seven of the fourteen astronauts from the MOL program were transferred to NASA, but the remaining research and equipment were jettisoned. NASA had one shot left at a space station. After Nixon had canceled the remaining three lunar missions, he agreed to use remaining Apollo hardware for a manned space station that would be called Skylab.14 Skylab would fly but would be parked in orbit after three visits awaiting the arrival of the Space Shuttle in 1979 to boost it to a high orbit. The Shuttle came too late to save Skylab. America’s first and only solely owned and built space station would come crashing down over the Indian Ocean and Australia in July of 1979. The second Skylab would never fly and became a museum artifact.

The Shuttle briefly gave the Air Force the manned space program longed for since the late 50’s; but after several missions, NASA and the Air Force would part ways and leave human spaceflight to the civilian program it had supported early in its history. Those early partnerships and dreams that each had of building America’s manned space capabilities would wither. NASA would go on to struggle with operating the Space Shuttle and America would lose the sustainable and flexible space program that fifty years later it seeks to create once again.

Sources:

1. Popular Mechanics, (2018), Is Russia’s Mysterious New Satellite a Space Weapon? https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a22739471/is-russias-mysterious-new-satellite-a-space-weapon/

2. SpaceNews, (2018), Some fresh tidbits on the U.S. military space budget. https://spacenews.com/some-fresh-tidbits-on-the-u-s-military-space-budget/

3. Union of Concerned Scientists, (2012), A History of Anti-Satellite Programs, https://www.ucsusa.org/nuclear-weapons/space-security/a-history-of-anti-satellite-programs#.W4wdbi2ZPYV

4. Cadbury, Deborah.(2007). Space Race: The Epic Battle Between America and the Soviet Union for Dominion of Space. New York: Harper, 2007.

5. Heppenheimer, T.A.(2007). 1999The Space Shuttle Decision NASA’s Search for a Reusable Space Vehicle. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Washington, D.C., http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4221/ch5.htm

6. Brzezinski, Matthew. Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries that Ignited the Space Age. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2007.

7. Keough, David . (2007). Army Turns over Ballistic Missiles to the Air Force and NASA. US Army Military History Institute, http://www.army.mil/-news/2007/10/14/5512-army-turns-over-ballistic-missiles-to-the-air-force-and-nasa/

8. Logsdon, John. Ten Presidents and NASA. Washington, D.C.:NASA, http://www.nasa.gov/50th/50th_magazine/10presidents.html

9. Air Force (1965). The Air Force in Space. USAF Historical Division. Washington, D.C.

10. Godwin, R., (2003). Dyna-Soar: Hypersonic Strategic Weapons System. Detroit: Apogee Books.

11. Zak, A., (n.d.). Origin of the Almaz Project. RussianSpaceWeb.com, http://www.russianspaceweb.com/almaz_origin.html

12. Baker, P., (2007). The Story of Manned Space Stations. Berlin: Springer.

13. Lambakis, S., (2001). On the Edge of Earth. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

14. Shayler, D., (2001). Skylab. Berlin: Springer.