Ferrying the Shuttle – Part Three: Hitching a Ride

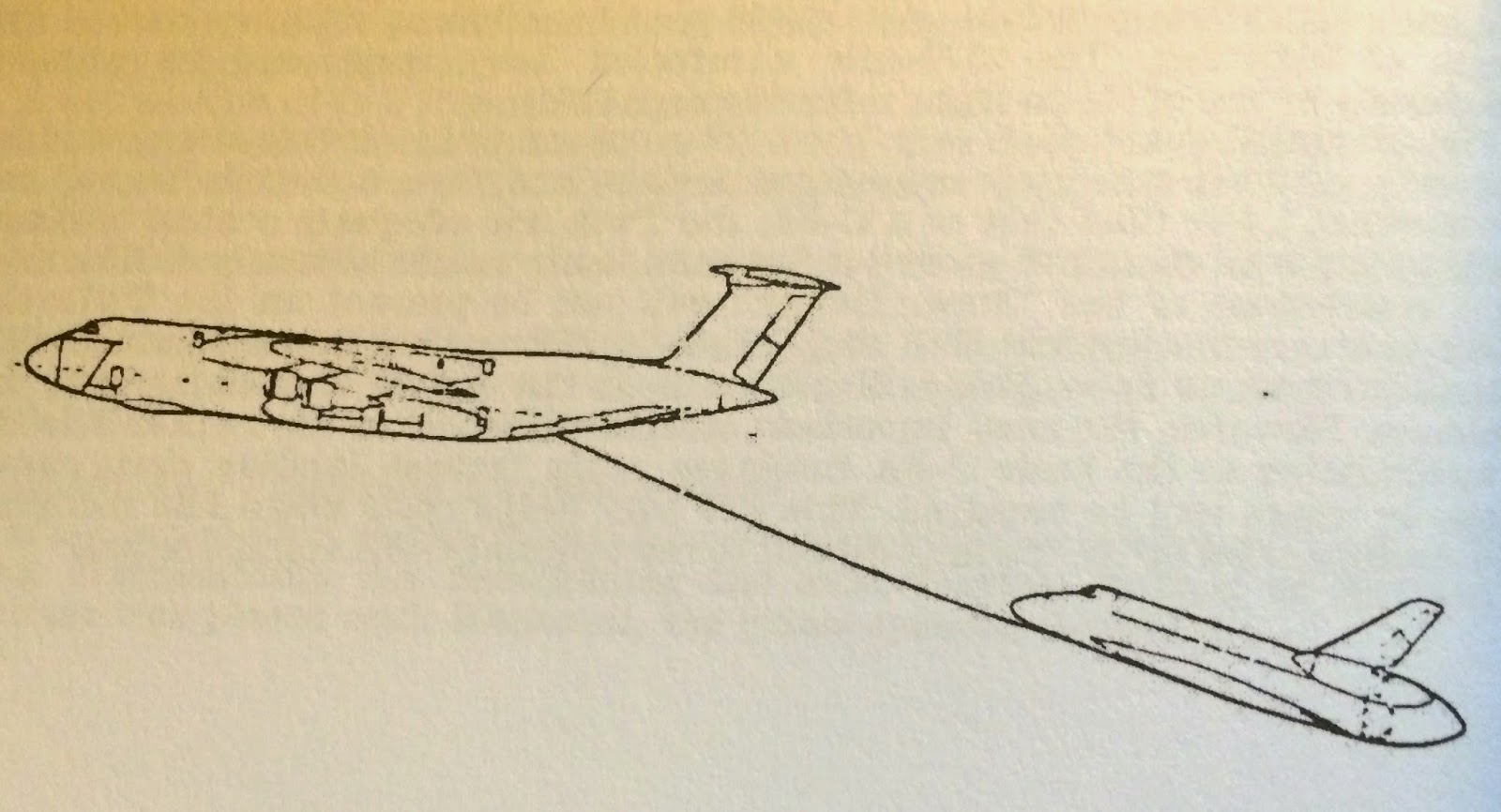

If the shuttle could not fly itself across the country then how do you get a spacecraft that weighs as much as a Boeing 757 from California to Florida? One idea proposed by Lockheed was to “tow” the Orbiter behind a C-5. This method would be used to ferry the vehicle and for drop tests. The plan called for a 1000ft cable linking the two, but doubts about the tension in the cable and the effect of jet wash on stability quickly nixed the idea. Despite the fact that Lockheed had faith in the concept, much like the other options on the table it seemed too risky an approach. In the event that the cable had to be detached in an emergency, or that it snapped in flight, the Orbiter would become a piloted glider with few options to maneuver to a suitable landing site. The outcome likely would have been the loss of the vehicle and possibly the loss of crew. NASA was searching for the middle ground trying balance the safety and protection of their newest spacecraft against the expense.

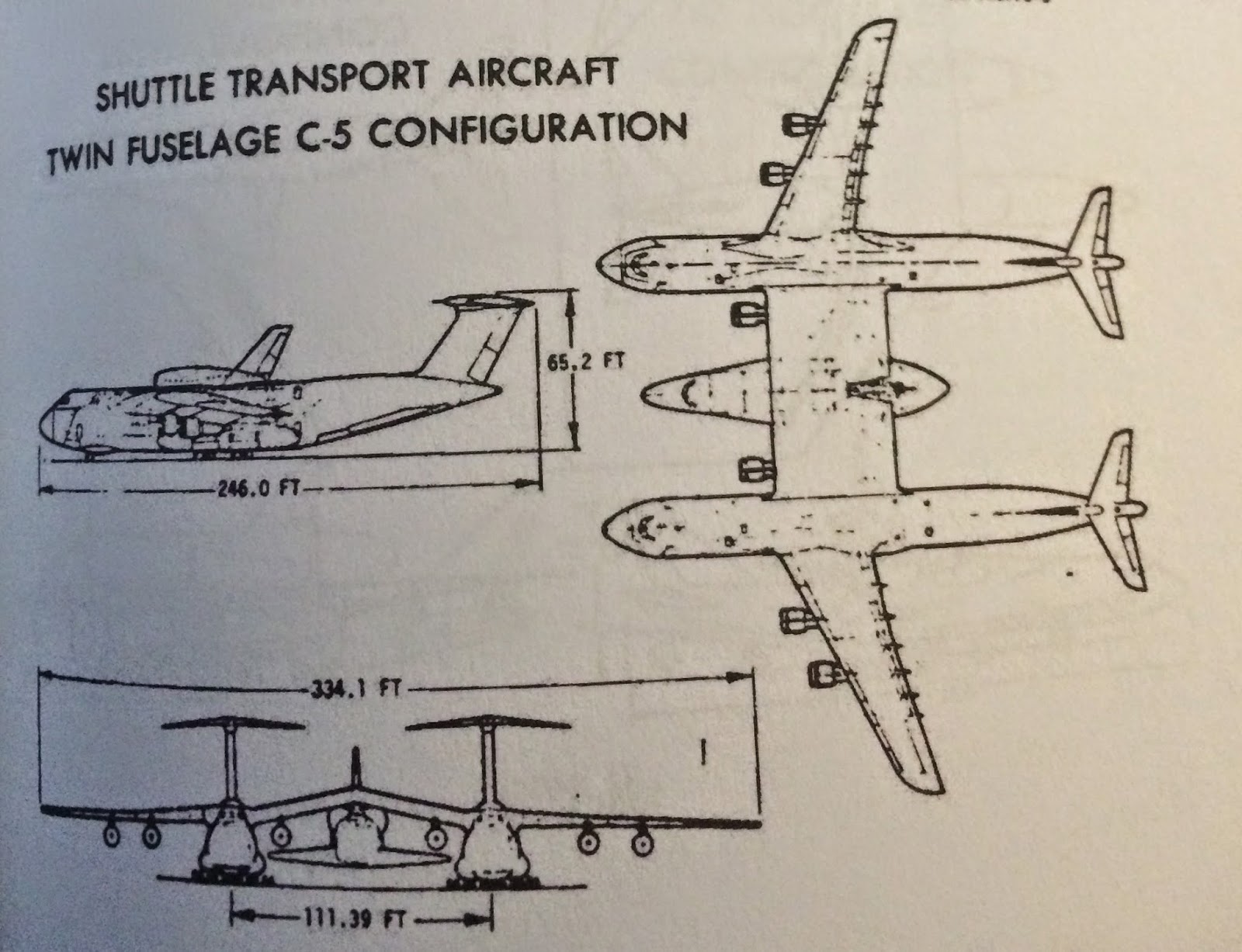

The inspiration that would lead to the final design would come from the X-15 program. It was suggested that perhaps the vehicle could be stowed under the wing of an aircraft and transported from site to site or used for drop tests similar to previous NASA test vehicles. The Orbiter is not an X-15, it is large and it is heavy. No aircraft existed that could carry the shuttle tucked under its wing like the X-15 was under a B-52. There was no shortage of other ideas. There was the concept of designing the Orbiter with removable wings or wings that could be “changed out” for ferry flights. That seemed to be too expensive and would likely add weight to support the attach and detach support structures. Given the size and weight of the Orbiter it would have to be centered underneath an aircraft. The only way that could be reasonably accomplished would be to build a plane with a twin fuselage joined by a straight center connecting wing and hang the Orbiter right in the middle.

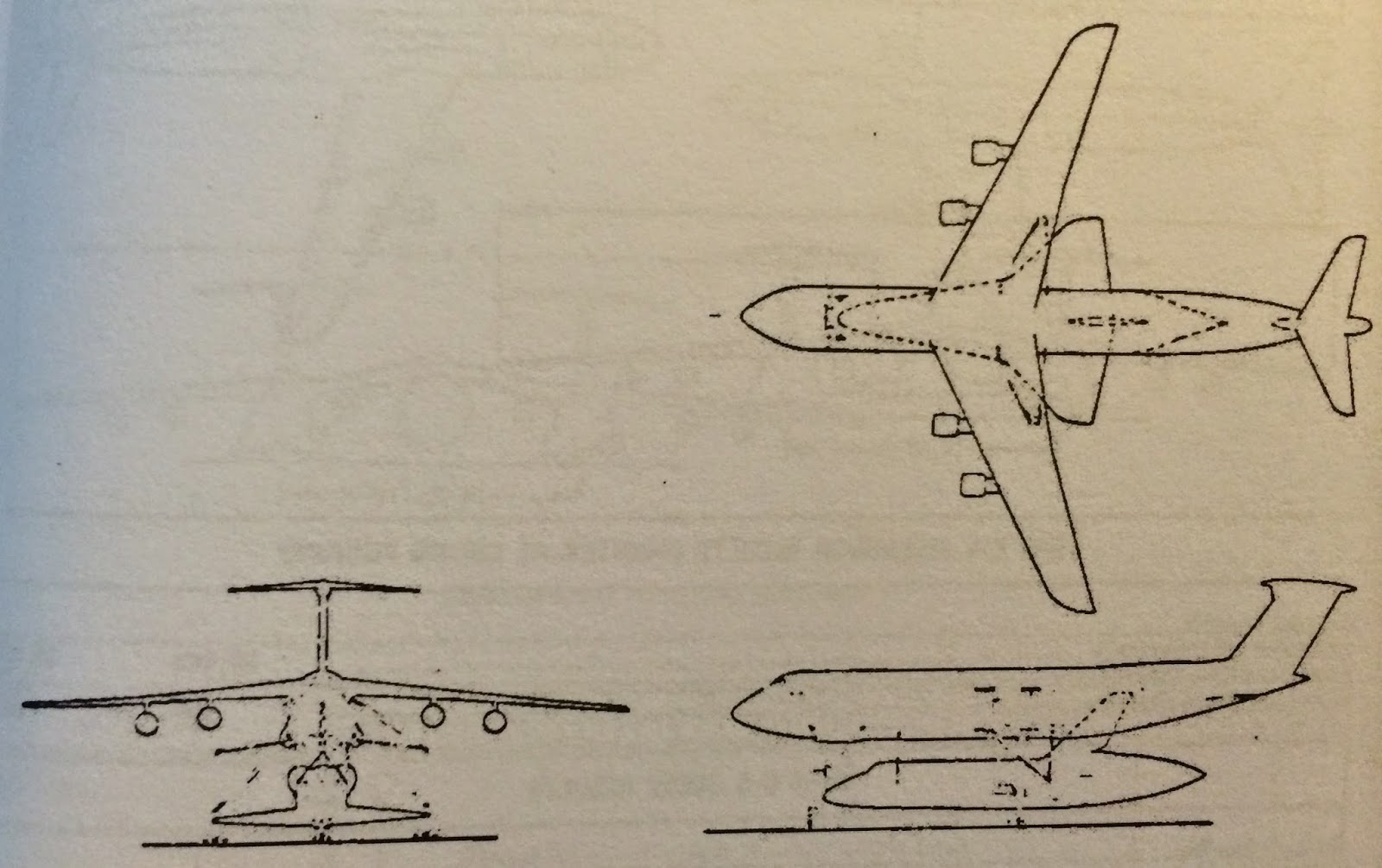

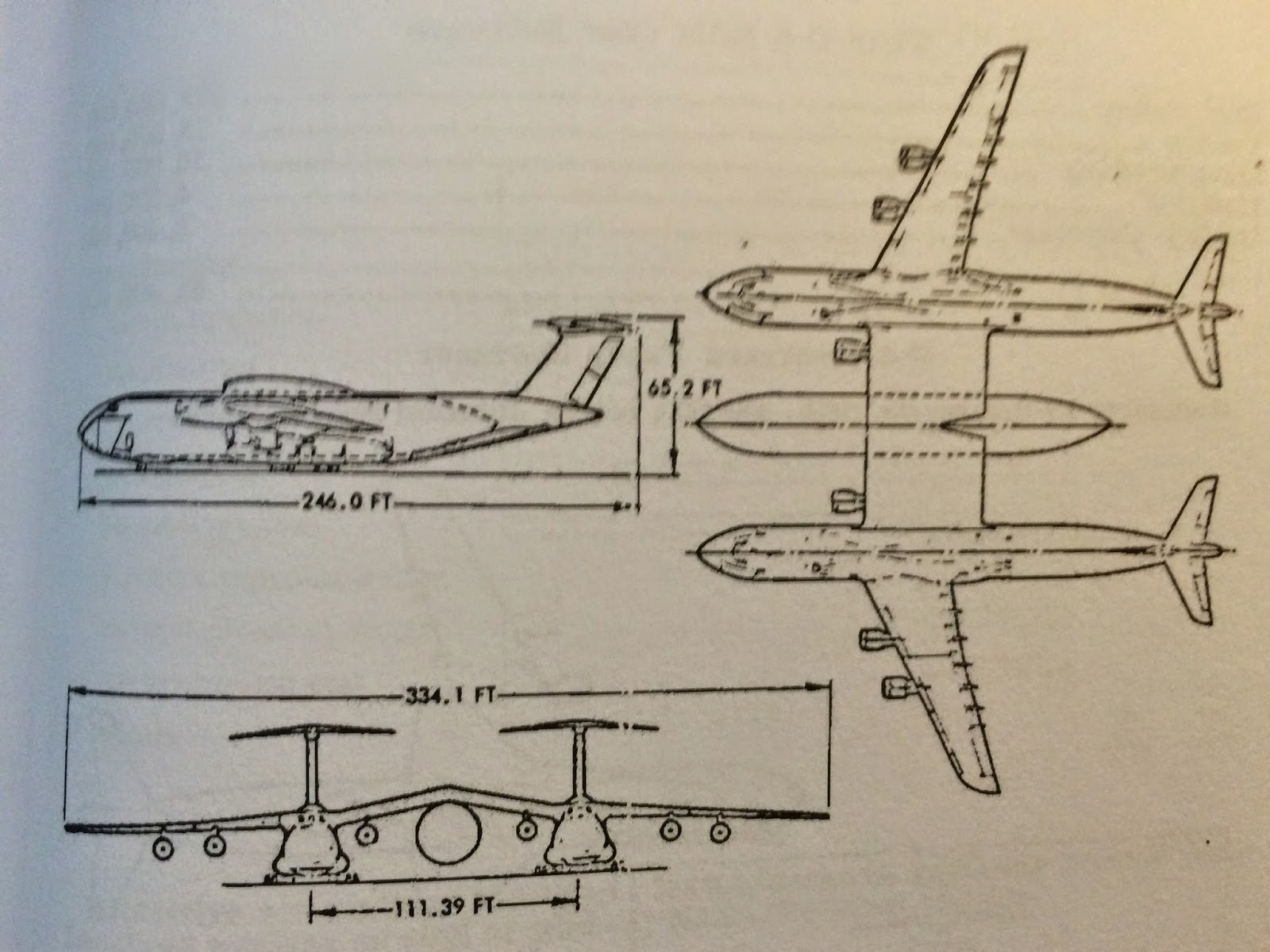

As the brainstorming continued, four options for this model were kicked around by engineers. The first would involve building a brand new one of a kind aircraft from scratch, but using “off the shelf” components. In this model, the ferrying aircraft would not need a twin fuselage, but would be low mounted in the center of the aircraft and the cockpit would be above the Orbiter. Picture the second story cockpit of the 747. Another concept dubbed the “long leg” approach called for center mounting the Orbiter underneath a C-5. To make room for the shuttle the C-5 would be equipped with extremely long landing gear to provide adequate clearance under the aircraft. Other ideas for ferrying a low, center-mounted shuttle involved using two 747s or two Air Force C-5 Galaxies. Under this plan, the 747s or C-5s would have a left and right fuselage and outer wing joined by a massive straight center wing. By any standards, this would have been the world’s largest aircraft, but it was not to be.

As the brainstorming continued, four options for this model were kicked around by engineers. The first would involve building a brand new one of a kind aircraft from scratch, but using “off the shelf” components. In this model, the ferrying aircraft would not need a twin fuselage, but would be low mounted in the center of the aircraft and the cockpit would be above the Orbiter. Picture the second story cockpit of the 747. Another concept dubbed the “long leg” approach called for center mounting the Orbiter underneath a C-5. To make room for the shuttle the C-5 would be equipped with extremely long landing gear to provide adequate clearance under the aircraft. Other ideas for ferrying a low, center-mounted shuttle involved using two 747s or two Air Force C-5 Galaxies. Under this plan, the 747s or C-5s would have a left and right fuselage and outer wing joined by a massive straight center wing. By any standards, this would have been the world’s largest aircraft, but it was not to be.

Another possible selling point to the low mounted Orbiter in this “twin” configuration was that it might have been possible to use the same aircraft to transport the shuttle’s external fuel tank on a separate flight. Some proposals called for such a capability.