Ferrying the Shuttle – Part Four: The Shuttle Carrier Aircraft

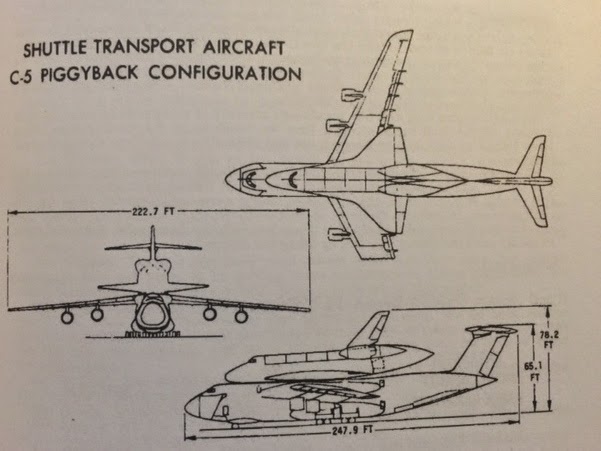

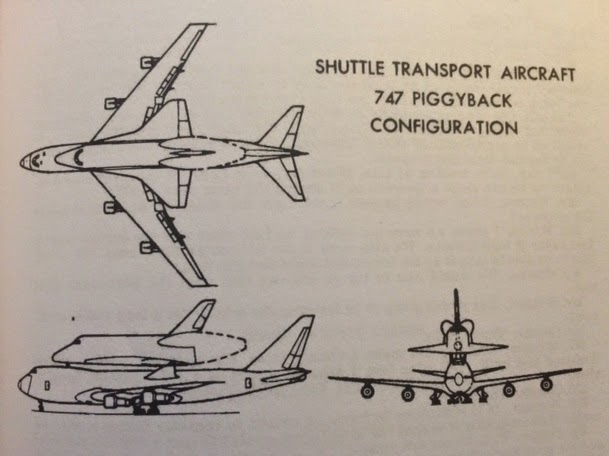

The bragging rights to carry the Shuttle on its back came down to the Air Force’s C-5 and Boeing’s 747. The C-5 was a potential budget buster for NASA. It was a large and expensive aircraft that entered production in 1968. The initial version of the aircraft had developed problems with cracks in the wings and it appeared that at least in the near term were likely to suffer a higher rate of fatigue. The aircraft also had a high wing design and a large T-tail which while not enormous drawbacks could have proved problematic. It should be noted that the Soviet Space Shuttle Buran successfully rode atop the high wing AN-225. The AN-225 has similar features to the C-5, but varied in design of the vertical stabilizer. While the C-5’s job was to haul heavy cargo, given the expense it was overkill for what NASA needed.

The bragging rights to carry the Shuttle on its back came down to the Air Force’s C-5 and Boeing’s 747. The C-5 was a potential budget buster for NASA. It was a large and expensive aircraft that entered production in 1968. The initial version of the aircraft had developed problems with cracks in the wings and it appeared that at least in the near term were likely to suffer a higher rate of fatigue. The aircraft also had a high wing design and a large T-tail which while not enormous drawbacks could have proved problematic. It should be noted that the Soviet Space Shuttle Buran successfully rode atop the high wing AN-225. The AN-225 has similar features to the C-5, but varied in design of the vertical stabilizer. While the C-5’s job was to haul heavy cargo, given the expense it was overkill for what NASA needed.

It would be a combination of factors that would ground the C-5 from consideration and push the 747 to the forefront. The availability, acquisition, operating, and maintenance costs of the C-5 were too big an obstacle for NASA to overcome. On June 17, 1974, less than a year after NASA signed the contract to put jet engines on the Orbiter for ferry and atmospheric testing flights, the debate was settled. In a press release NASA announced that Boeing 747 would now get the call and become the Shuttle’s chauffeur when it needed a ride.

Solving the problem of how to ferry the shuttle was perhaps a foreboding sign of how challenging getting the Space Shuttle off the ground would turn out to be. In less than a year, the Orbiter went from having jet engines installed between missions to ferry itself to riding on atop a 747. Now, all NASA needed to do was find a bargain priced 747 and make sure the modifications to the aircraft could be made and that the plan would work.

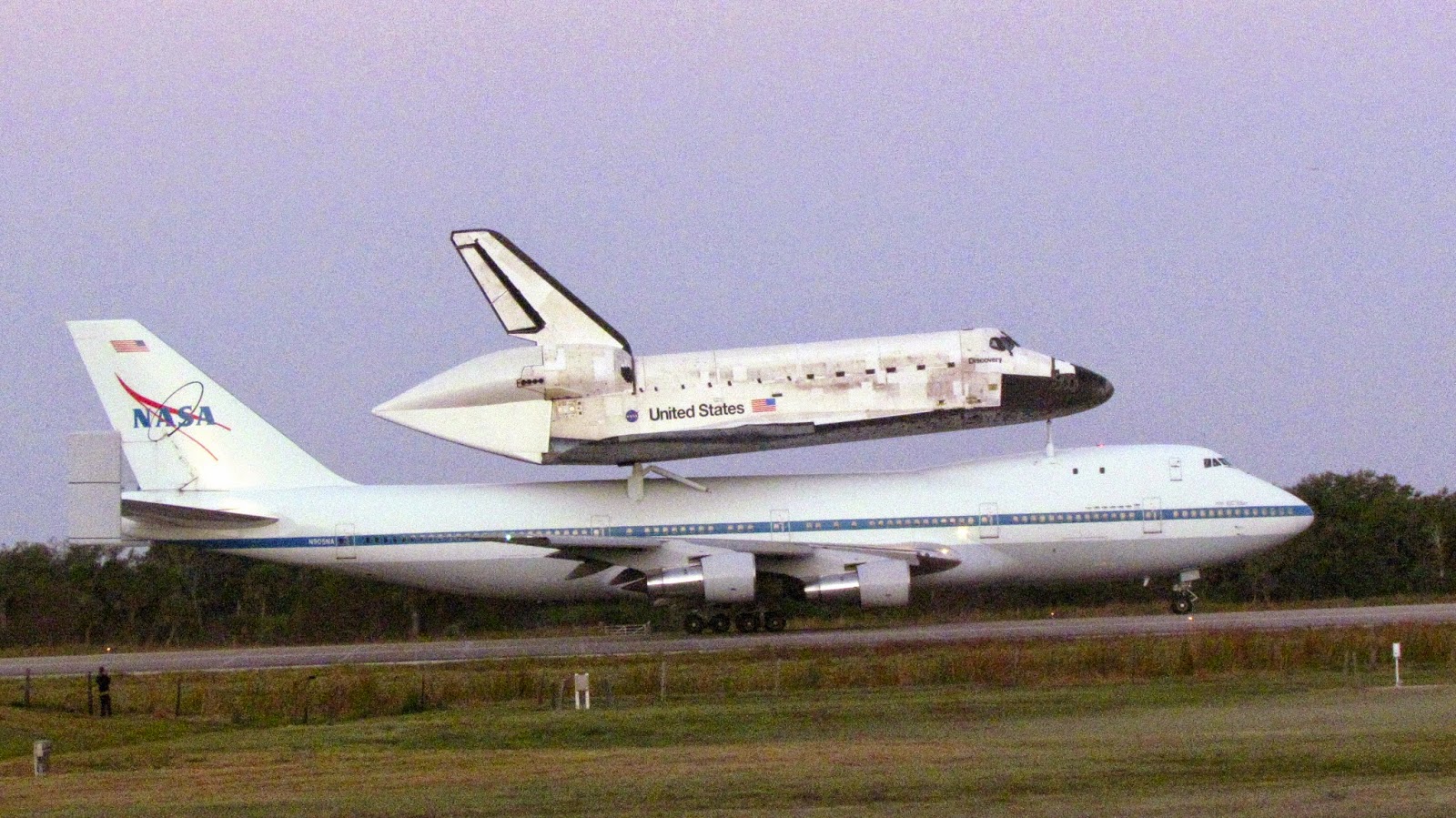

In that same year, NASA acquired a used 747 from American Airlines for $16 million. The aircraft, built in 1970 for passenger service, would become NASA 905 with tail number N905NA. It was put to work immediately as part of a study to understand the effect of wing vortices on trailing aircraft. In 1976, it was sent to Boeing to undergo modifications in preparation to carry the shuttle on the first approach and landing tests. The modifications included stripping the interior to reduce weight, adding the Orbiter’s attach points and strengthening the fuselage. Its only job would be to carry the spacecraft anytime it needed to move from west to east, or on its last flights take the Orbiters home to their final resting place. In 1998, NASA acquired a second used 747 from Japan Airlines, It would become N911NA.

A mate-demate scaffolding like structure was built to lift the Orbiter on to the back of the 747. These mate-demate structures we housed at the Kennedy Space Center and Armstrong Flight Research Center (formerly Dryden). Only one time in the operation phase of the program were the devices not used. That occurred on STS-3 when Columbia landed at the White Sands Test Facility, Special equipment was shipped by train to the site to lift the Orbiter on to the 747. It would not be used again until the flight ferry flights of Discovery, Endeavour, and Enterprise to museums in Virginia, California, and New York. The older NASA 905 would be the workhorse from start to finish. The newer NASA 911 would retire early and NASA 905 would take finish the job it started three decades earlier without a hitch giving the Orbiters one last ride.

A mate-demate scaffolding like structure was built to lift the Orbiter on to the back of the 747. These mate-demate structures we housed at the Kennedy Space Center and Armstrong Flight Research Center (formerly Dryden). Only one time in the operation phase of the program were the devices not used. That occurred on STS-3 when Columbia landed at the White Sands Test Facility, Special equipment was shipped by train to the site to lift the Orbiter on to the 747. It would not be used again until the flight ferry flights of Discovery, Endeavour, and Enterprise to museums in Virginia, California, and New York. The older NASA 905 would be the workhorse from start to finish. The newer NASA 911 would retire early and NASA 905 would take finish the job it started three decades earlier without a hitch giving the Orbiters one last ride.

The Space Shuttle Orbiter sitting atop a Boeing 747 was a memorable sight.  Its last trip made a lasting impression as it performed flybys to crowds in cities like Houston, Austin, Washington, and New York that were awed by the sight of these two historic feats of engineering that were dependent on each other. Starting with the very first space shuttle, Enterprise to the last shuttle Endeavour, every Orbiter needed the Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) to go anywhere but space. After more that 30 years of service their work was done. With nowhere left to fly the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft NASA 905 joins the Orbiters in the history books and will now go on display at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Its last trip made a lasting impression as it performed flybys to crowds in cities like Houston, Austin, Washington, and New York that were awed by the sight of these two historic feats of engineering that were dependent on each other. Starting with the very first space shuttle, Enterprise to the last shuttle Endeavour, every Orbiter needed the Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) to go anywhere but space. After more that 30 years of service their work was done. With nowhere left to fly the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft NASA 905 joins the Orbiters in the history books and will now go on display at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Figuring out how to ferry a Space Shuttle got off to a rough start, but in the end it turned out to just turned out to be all in a day’s work for the Boeing 747.